Memorial products and funerals have changed a lot in the past 20 years. With the advent of the internet, it’s even easier to get unique and meaningful memorial products. But 200 years ago people did things a little differently. Here’s a look at five weird vintage funeral products.

Safety Coffin

Taphophobia is the fear of being buried alive and prior to modern medicine it was something that people were genuinely concerned about. There have been accounts of people being buried alive since the 14th century. Edgar Allen Poe even wrote about this fear in his short story called “Premature Burial,” where a narrator makes his friends promise to not bury him prematurely and builds a tomb that gives him the ability to signal for help.

In 1868, the first patent for an “Improved Burial-Case” was granted to Franz Vester. His invention included a ladder so the person could escape and a bell to alert those around the grave in case the person was too weak to climb out. There was also an air inlet so in case someone was accidentally buried prematurely, they wouldn’t suffocate inside of their casket.

Hair Jewelry

When Queen Victoria’s husband Prince Albert died in 1861, she publicly mourned him until she died 40 years later. Part of her mourning was wearing a lock of her husband’s hair in a necklace. She greatly influenced the customs for grieving women during the era. In the United States, women started getting more creative with the hair from deceased loved ones.

People made wreaths, rings, necklaces, and more out of human hair. There were even books written to instruct people at home how to do hairwork. Often hair from the living and the dead would be woven and braided together into complex flowers and vines. Since most Victorians held their funerals in the home and were close to their dead, it wasn’t seen as morbid to snip a lock of hair from the deceased. Hairwork went out of fashion in the 1920s with the advent of funeral homes.

O. Henry Museum in Austin Texas

Mortsafes

People that lived in Scotland in the early 19th century had to take some extra precautions to make sure their loved ones stayed resting in peace. Before 1832, the only way for anatomists to obtain cadavers to study was to use the bodies of executed criminals donated by the government. These bodies were still difficult to obtain because the public was largely opposed to dissection. Because of the shortage, students turned to buying recently deceased corpses that were dug up and sold by body snatchers.

Residents of Edinburgh took protecting their deceased loved ones by investing in “mortsafes.” These could be a heavy stone table, a concrete box, or even an iron cage surrounding the burial site. Communities also created watch groups to monitor graveyards at night. The need for mortsafes stopped when the Anatomy Act was passed in 1832 which made it legal for anatomists to obtain cadavers. Several intact mortsafes can still be seen in old church cemeteries around Scotland.

Mortsafe at Greyfriars Cemetery

Airtight Coffin

In 1848 a man named Almond Fisk patented a design for a coffin that was unusual to say the least. The ”Fisk Airtight Coffin of Cast or Raised Metal” was an ornate cast-iron coffin that was made for transporting corpses and to keep from spreading diseases like yellow fever or cholera. The coffin was often decorated with roses, angels, and thistles overtop of an iron shroud. Fisk hoped that his design would lessen “the disagreeable sensation produced by the coffin on many minds.”

Unfortunately for Fisk, people found the coffins to be creepy. A window was added to the top of the case so mourners could look at the face of the departed which didn’t make them any less unsettling. People nicknamed the coffins “Fisk Mummies” since they were reminiscent of ancient Egyptian sarcophagi. On top of people not liking how they looked, they were also prone to exploding. As the corpse would decay, pressure would build inside of the iron coffin, causing them to burst. The exploding was reported on by the Chicago Press in 1858 and refuted by the manufacturers of Fisk’s Metallic Burial Case in the New York Times. Production stopped on the coffins in 1860 and are an incredibly rare find.

“Fisk Mummy” in the Memphis Pink Palace Museum

Death Masks

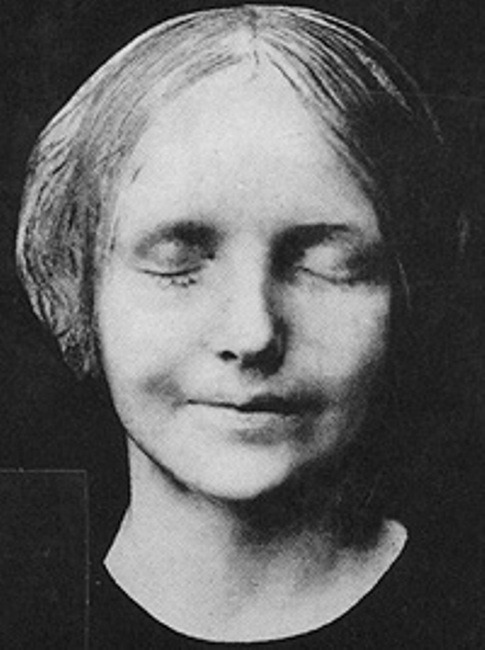

Death Masks were first made by the ancient Egyptians and Africans as a spiritual ritual. They became memorials of the dead in the middle ages. They started to grow in popularity in the late 19th century after a mask was made from a woman that had drowned from the Seine River in Paris.

Death masks are made a few hours after death so that post-mortem bloating didn’t interfere with the mask. A physician would grease the face to keep the skin and facial hair intact and then cover the face in plaster bandages to make a mold. After the plaster had set, the mold was removed and filled with wax or clay, metal, or plaster.